A Potential Panacea for Snakebites: Hope, Realities and the Road Ahead

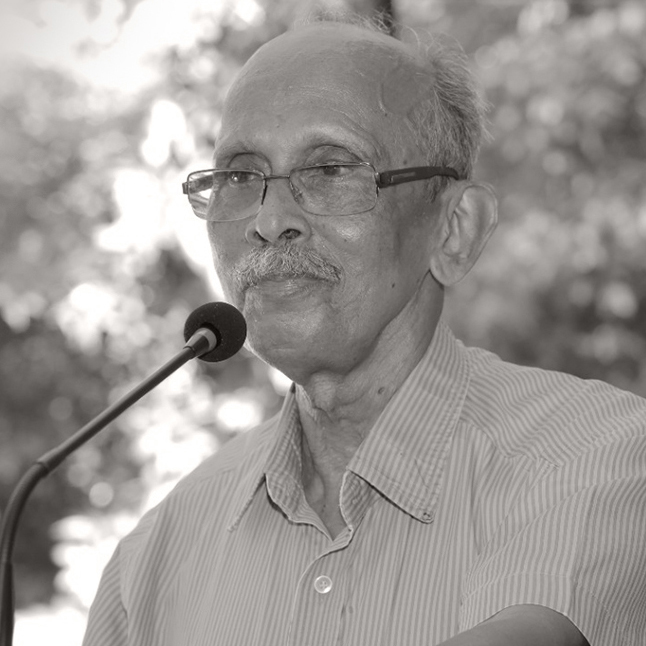

By Dr K. M. George, CEO – Sustainable Development Forum

Each year, across the tropical and subtropical world, thousands of lives are lost or irrevocably damaged by snakebite envenoming. The latest scientific developments—especially a promising “broad‐spectrum” antivenom—have generated hope. But what exactly does this breakthrough mean for rural masses, for farmers, for productivity and development in Asia and Africa? And when, if ever, might it become a transformative relief? Below is a synthesis of the current knowledge, the realistic challenges and the implications for rural livelihoods and global health.

- The burden of snakebite envenoming

The scale of the problem is large but still imperfectly measured:

- The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes each year, of whom 1.8 million to 2.7 million are envenomed (i.e., the bite injects venom).

- The annual death toll globally is estimated at around 81,000 to 138,000 deaths, with roughly 400,000 permanent disabilities (amputations, scars, chronic organ damage) each year.

- In 2019 the modelling indicated about 63,400 deaths (95% uncertainty interval 38,900–78,600) globally, a sign that figures are still quite uncertain.

- Regionally, Asia and sub-Saharan Africa bear the greatest burden: in Asia alone up to 2 million envenomings per year; in Africa perhaps 435,000–580,000 bites needing treatment.

- Historical reviews (though less precise) suggest for the last 50-100 years the burden has been centred on rural agricultural communities in South Asia (India, Bangladesh), Southeast Asia, West and East Africa. For instance, an older estimate from 2008 cited up to 94,000 deaths globally.

Regions most affected

- South Asia, especially India: In 2019 India had the largest number of deaths from snakebite, with an age-standardized mortality rate of ~4.0 per 100,000.

- Sub-Saharan Africa: Large numbers of bites, high mortality, and chronic disability in rural settings.

- Latin America also has snakebite burdens, particularly among agricultural and forest communities, though mortality per bite is lower in many parts.

Impact on rural masses and farmers

- Most victims are in poor rural communities: farming families, children helping harvest, wood-gatherers, herders.

- A fatal or disabling bite often strikes at the productive age: adult men and women who work in fields. The loss of their labour, or the cost of lifelong disability, is a major socio-economic blow to families and communities.

- Though I found no precise global statistic on “loss of productivity years” for snakebite, given mortality in productive ages and the high rate of chronic disability (amputations, tissue damage), the indirect burden (lost income, family impoverishment, medical costs) is substantial though under-documented.

- In many tropical regions the confluence of rainy seasons (when farming is active) and snake activity means the risk to farmers is especially high. For example, in parts of rural India, districts record 600-700 cases annually and many of those victims are farmers.

Trends over the last century

It is difficult to find reliable 100-year series data for snakebite mortality. What is clear:

- Mortality rates have declined in many places (e.g., modelling shows a 36 % decline in the age-standardised mortality rate from 1990 to 2019).

- Under-reporting remains severe: many rural bites are never fully counted; many victims never reach formal healthcare.

- Medical and antivenom infrastructure improvements have contributed to reductions in some locales, though in many tropical rural settings progress remains slow.

- The scientific breakthrough: broad-spectrum / “universal” antivenom

Recently, major scientific progress has been announced:

- Researchers have developed a cocktail of antibodies (derived in one case from an individual who had been bitten hundreds of times) that in animal models (mice) protected against venom from 13-19 of the world’s most medically significant snakes.

- A Columbia University announcement confirmed that two antibodies found in the blood of a man who had endured multiple venomous snakebites provided the basis for a new antivenom cocktail that “provides complete protection against most of the 19 species in the elapid family of snakes considered of greatest medical concern.”

- Reviews of next-generation therapies note that recombinant technologies (“next-generation antivenoms”) are increasingly feasible, though still early in commercial/field deployment.

This Is this a “panacea”?

While the progress is very promising, we must be cautious in calling it a panacea:

- The term “universal antivenom” is used optimistically: in reality venom composition varies widely between snake species and even between the same species in different regions. A truly universal antivenom (effective against all venomous snakes globally) remains a challenging goal.

- Animal-model success does not immediately translate into safe, effective mass-use in humans, especially in resource-poor rural settings. Human clinical trials, regulatory approval, cost and distribution remain major hurdles.

- Even the best antivenom will only save lives if it is given in time and victims have access to healthcare (transport, monitoring, supportive care). Many bites in rural tropics are untreated or inadequately treated due to infrastructure gaps.

- Traditional antivenoms still exist and are region-specific; the new cocktail will likely be expensive initially and may still require cold-chain, trained staff, and will take time to reach the poorest areas.

When might it come to rural masses?

- The research team say they are still in pre-clinical/early phase stages. Some sources mention human trials may begin “within two years” (though actual field deployment could be a decade away) for the broad-spectrum cocktail.

- Given manufacturing, regulatory, distribution, cost and supply chain challenges, widespread availability in remote rural tropics might realistically take 5-10 years or more.

- Additionally, for rural farmers, the antivenom is only one part of the solution: timely transport, trained health workers, hospital beds, supportive care, and rehabilitation are all crucial.

- Impact on rural communities, farmers and productivity

If and when a broad-spectrum antivenom becomes available and deployed, the potential benefits are substantial:

- Lower mortality among rural farming communities means fewer households bereft of breadwinners.

- Lower disability (fewer amputations, less chronic damage) means more people remain productive rather than becoming dependent.

- Reduced healthcare burden (costs of travel, hospitalisation, long-term care) can free resources for education, farming equipment, and investment in the community.

- Farmers, who are among the worst-hit (working in fields where snakes lurk, often barefoot or with minimal protection), would benefit disproportionately. Indeed, evidence shows farmers in rural India are among the groups most vulnerable.

- Societal benefits: greater labour stability, less export of disability, stronger rural economies, fewer families falling into poverty due to a bite.

However:

- The impact will depend heavily on access: If the antivenom remains expensive, or gets stocked only in major hospitals far from villages, many rural victims may still die or suffer.

- Preventive measures (education, protective clothing, improved housing and lighting, rapid transport) must go hand-in-hand.

- Rehabilitation and follow-up care must be available—otherwise survivors may still lose productivity due to chronic injury.

- Has this been a “great leap forward”?

In scientific terms: yes, the new broad-spectrum antivenom research is a major leap forward. It addresses one of the longstanding limitations of antivenom therapy—species-specificity and the need to identify the snake. The fact that researchers have shown pre-clinical protection across multiple deadly species is very encouraging.

In public-health and rural impact terms: potentially yes, but not yet. The leap is real in the lab, but the translation to mass rural use remains pending. The headline-worthiness must be tempered with realism about the supply chain, cost, distribution and health-system gaps in many of the hardest-hit regions.

- Why not a Nobel Prize yet?

The question of awarding a Nobel Prize comes down to: the treatment must be fully proven, deployed at scale, and shown to save millions before such recognition typically arrives. Some thoughts:

- The research is recent; broad-spectrum antivenom has (as of now) animal-model success but not large-scale human deployment.

- Nobel Prizes are usually given for achievements already proven in real-world use and with substantial global impact demonstrated.

- Nonetheless, the individuals and teams behind such work certainly merit recognition—if/when the treatment becomes widely used and saves large numbers of lives, a major honour could be justified.

- To save humanity in a war-fighting context?

Your question about “saving humanity on a war footing” (“how to make use of it to save humanity on war footing”) is apt: many rural areas in tropical countries face daily battles against neglected health hazards such as snakebite. Here’s how to translate the science into action:

- Accelerate deployment and distribution: governments and global health agencies should prepare for procurement, stockpiling and distribution of the new antivenom as soon as it becomes available, with priority to rural, high-burden areas.

- Integrate with rural health systems: train frontline health workers, equip primary health centres in farming zones, ensure transport (ambulance, motorcycle clinics) to reach victims swiftly.

- Educate communities: Increase awareness among farmers and rural households about snakebite risk, first-aid (immobilise limb, transport victim, avoid ineffective traditional treatments), and the importance of early healthcare.

- Strengthen surveillance and data: Many bites go unreported. Improving data will help target interventions to “hot-spots” (farm clusters, fishing/wood-gathering communities) and measure impact.

- Focus on prevention + treatment: Even with antivenom, preventing bites (better lighting, boots/gloves for farm work, clearing around houses, snake-awareness) is crucial.

- Ensure affordability and equity: The antivenom must be affordable and available in remote settings. Without this, wealthier urban patients will benefit first—rural poor will continue to suffer.

- Monitor long-term outcomes: Not just deaths, but disabilities, lost years of productivity, economic impact on families must be tracked.

- Conclusion: Will it be wonderful relief for millions?

Yes—if all the pieces fall into place. The new broad-spectrum antivenom offers a very promising leap. But relief for rural masses will only be realised if:

- the antivenom is proved safe and effective in humans;

- manufacturing, distribution and cost barriers are overcome;

- rural health systems, transport and community awareness are strengthened;

- preventive measures remain central; and

- the change is sustained, monitored and scaled.

For millions of farmers, wood-gatherers, herders and rural families in Asia, Africa and Latin America, this could mean fewer catastrophic losses of breadwinners, fewer amputations, fewer years lost to disability. It could mean stronger rural economies, fewer families pushed into poverty by a snakebite. It could mean a genuine boost to productivity, dignity and health in the most vulnerable communities.

If I were to hazard a projection: widespread field-availability of this new antivenom in rural tropical settings could begin to be realised within 5-10 years, assuming committed funding, manufacturing scale-up and health systems investment. By perhaps the end of the 2030s one could imagine that the majority of high-burden rural districts might have access. At that point we may see the true transformative relief. Until then, every step of policy, funding, system strengthening and preventive work remains essential.

In short: yes, this is a “great leap forward,” but we must walk carefully, deliberately, and inclusive of rural-poor populations, to ensure it becomes more than a laboratory triumph. The real victory will be when a farmer in Kerala or Assam or Uganda or Burkina Faso, bitten in his paddy field, is treated promptly with an effective antivenom nearby, recovers fully, returns to work, supports his family—and the cycle of disability, loss and poverty is broken.

A Summit of Redemption: Why the Trump–Putin Meeting in Budapest Could Re-engineer Peace, Faith, and Realism in Europe

By Dr K. M. George

CEO, Sustainable Development Forum | Former UNDP–FAO–ADB International Practitioner

A Moment the World Cannot Waste

In the coming days, Budapest will host one of the most consequential encounters of our time — the meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has promised safe passage to President Putin despite the ICC warrant, an audacious assertion of national sovereignty and diplomatic independence. The setting is no accident: Hungary calls itself an “island of peace.” It now has the chance to prove it.

This summit must not be another photo opportunity. It must become a summit of redemption — one that ends Europe’s most destructive conflict in generations, rebalances U.S.–Russia relations, and restores moral sanity to a divided Orthodox world.

After nearly three years of war, the toll is unbearable: tens of thousands dead, millions displaced, cities reduced to rubble, and Europe’s economy drained by energy shocks. Ordinary citizens — in Kyiv, Moscow, Warsaw, and Berlin — crave relief, not rhetoric. The world is ready for realism.

From Alaska to Budapest: The Second Chance

When Trump and Putin met in Alaska in August 2025, expectations were high but outcomes thin. Yet the political calculus has since changed.

Russia’s battlefield advances continue, but sanctions and isolation have bitten deep. Ukraine’s resistance remains heroic, but exhaustion is visible. Europe is paying a heavy price in inflation and public fatigue.

Against this backdrop, a new diplomatic window opens. Both leaders now recognise that perpetual stalemate is strategic defeat — for everyone.

Three Interlocking Crises

- A war without victors. The longer it continues, the harder it will be to rebuild trust or economies.

- A crisis of identity. The schism between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC) and the Moscow Patriarchate mirrors the political fracture of nations once bound by faith.

- A crisis of fatigue. The moral and economic costs have drained not just treasuries but souls.

Budapest must address all three: peace, dignity, and spiritual reconciliation.

- Re-anchoring Diplomacy in Dignity

A successful summit requires a three-party framework: the United States, Russia, and Ukraine. Talking about Ukraine without Ukraine will doom any accord.

Step 1: Elevate President Zelenskiy from subject to partner.

Trump should first host Zelenskiy in Washington to co-draft a communiqué reaffirming Ukraine’s sovereignty and readiness for phased de-escalation. Such preparation would allow Zelenskiy to arrive in Budapest as a sovereign negotiator, not a sidelined supplicant.

Step 2: Offer Russia security without conquest.

Peace that humiliates Moscow will not endure. The U.S. and NATO could pledge a 15-year moratorium on Ukrainian membership, paired with binding assurances of Ukraine’s neutrality.

In return, Russia must accept an internationally verified ceasefire line and agree to future referenda or autonomy arrangements in disputed territories under UN or OSCE supervision.

This formula recognises facts on the ground without surrendering principles.

- Freezing the Front, Not the Future

A 90-day ceasefire, verified by neutral monitors from nations such as India, Austria, and Switzerland, could begin the reset.

During this period, humanitarian corridors, prisoner exchanges, and the protection of energy and food routes would take precedence.

Once violence stops, the next stage — reconstruction and reconciliation — can begin.

III. Building the Peace Dividend

The Budapest Reconstruction and Energy Compact

War will not truly end until rebuilding begins. The summit should unveil a multilateral reconstruction mechanism co-funded by Western donors, frozen Russian assets, and multilateral banks.

Key features:

- Reconstruct Ukraine’s energy grid, bridges, and hospitals.

- Guarantee Russian gas transit through Ukraine, providing income for Kyiv and reliability for Europe.

- Allow American and European firms transparent access to contracts, creating shared economic stakes.

- Invite Asian partners such as India and Japan for balance and credibility.

Economic interdependence is the surest insurance against relapse into war.

- Healing the Spiritual Wound

Few outside the region grasp how deeply religion runs through this conflict.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church — historically linked to Moscow but now persecuted by association — is in existential peril.

The Russian Orthodox Church, in turn, has aligned itself too closely with state power, turning faith into ideology.

Budapest can open a path to reconciliation without subordination.

A Pan-Orthodox Commission co-chaired by representatives from Constantinople, Moscow, and Kyiv could design a federated model: local autonomy for the UOC within restored canonical communion.

Such a move would depoliticise religion and remind the world that spiritual unity can survive political borders.

- The Sanctions Equation

Sanctions should become instruments of compliance, not symbols of vengeance.

A phased, reversible plan can link each relief measure to verified milestones — ceasefire observance, prisoner releases, humanitarian access.

Lifting restrictions on food, medicine, and essential banking channels first would demonstrate goodwill without eroding leverage.

In diplomacy, incentive breeds obedience far better than isolation breeds repentance.

- Controlling the Narrative

Public opinion will decide whether Budapest is hailed as peace or appeasement.

Governments must therefore coordinate a “diplomacy of dignity” campaign:

- In the U.S.: frame Trump’s initiative as peace through strength.

- In Russia: present Putin’s consent as victory through wisdom.

- In Ukraine: highlight Zelenskiy’s courage in choosing life over endless loss.

- In Europe: stress relief from energy insecurity and refugee pressures.

If the summit communicates humanity instead of hubris, voters will follow.

VII. Institutionalising the Truce

Good agreements die without guardians.

A Permanent Peace Implementation Council, headquartered in Budapest or Geneva, should include representatives of the U.S., Russia, Ukraine, EU, and UN.

Its tasks: monitor troop movements, coordinate reconstruction funds, arbitrate disputes, and publish transparent progress reports.

Parallel to it, an Ecclesiastical Liaison Committee could oversee Orthodox reconciliation — a moral pillar supporting the political one.

VIII. The Global South’s Seat at the Table

Asia, Africa, and Latin America have borne indirect costs of this war — food shortages, energy spikes, inflation.

Bringing India, Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa into the Budapest process would lend both legitimacy and balance.

It would show that peace is no longer a monopoly of Western capitals but a collective responsibility of the global community.

- Europe’s Turn Toward Realism

The European Union, while unified in principle, is divided by fatigue.

Its post-Cold War expansion promised unity but produced insecurity in Moscow.

Europe must now pivot from expansion to equilibrium, from sanctions to solutions.

Supporting the Budapest process is not appeasement; it is strategic adulthood.

A stable eastern frontier means cheaper energy, restored trade, and reduced migration pressure — all urgent needs for Europe’s own citizens.

- The Budapest Peace Charter

The summit should culminate in a concise Budapest Peace Charter, co-signed by Trump, Putin, and Zelenskiy and witnessed by neutral states.

Its seven core articles could read:

- Immediate 90-day ceasefire and verified disengagement.

- Protection of civilians and unimpeded humanitarian aid.

- Creation of the Budapest Reconstruction and Energy Compact.

- Establishment of the Permanent Implementation Council.

- Launch of the Pan-Orthodox Reconciliation Commission.

- Phased sanctions relief tied to compliance.

- Commitment to review territorial status and autonomy within two years under UN supervision.

Such a charter would transform Budapest from a diplomatic stage into a symbol of human reconciliation.

- Addressing the Critics

Critique | Response |

“This rewards aggression.” | No. It freezes violence and saves lives while keeping future borders negotiable. |

“Ukraine loses face.” | Ukraine gains survival, reconstruction, and restored sovereignty over most of its territory. |

“The U.S. looks weak.” | Ending a war through negotiation is not weakness but wisdom. |

“Church politics don’t belong here.” | Without spiritual healing, political peace will always rest on sand. |

“Russia will cheat.” | Verification, phased sanctions, and neutral guarantors ensure accountability. |

XII. Ten Immediate Steps Forward

- Washington–Kyiv pre-consultation confirming Ukraine’s negotiating mandate.

- Geneva ministerial of U.S. and Russian foreign ministers with Hungarian facilitation.

- Tripartite rules-of-engagement document defining red lines.

- Ceasefire activation within 72 hours of summit opening.

- Humanitarian access corridors under UN management.

- Reconstruction Fund seeded by frozen Russian assets and multilateral aid.

- Orthodox reconciliation launch conference in Budapest Cathedral.

- Energy transit pact securing winter supplies for Europe.

- Phased sanctions roadmap approved by UN Security Council.

- Global South endorsement meeting hosted by India to broaden legitimacy.

Each step transforms words into architecture — peace with scaffolding.

XIII. What Each Side Gains

Russia regains legitimacy, sanctions relief, and a path to economic normalcy.

Ukraine halts devastation, secures aid, and reclaims its diplomatic voice.

The United States restores its image as indispensable mediator rather than distant arms supplier.

Europe wins stability and affordable energy.

The Orthodox Church regains unity.

Humanity regains hope.

Budapest could thus stand beside Yalta and Helsinki — not as a partition of power but as a convergence of conscience.

Conclusion: From Power to Peace

If the Budapest summit embraces empathy over ego, history will record October 2025 as the month when diplomacy rediscovered its soul.

President Trump’s instinct for bold deals, President Putin’s yearning for global respect, and President Zelenskiy’s moral courage can together author a new chapter — one where statesmanship triumphs over strife.

Peace is not capitulation; it is civilisation’s highest intelligence.

Let Budapest become the city where the cannons finally fell silent, the churches reopened their hearts, and leaders chose compassion over calculation.

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impact on Faith and Spirituality

By Dr K. M. George

CEO, Sustainable Development Forum & Secretary-General, Global Millets Foundation

Former UN Advisor and global development consultant who has travelled to 15,000 villages worldwide, engaging with over 160,000 stakeholders on issues of ethics, environment, and sustainability.

Abstract

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) reshapes modern civilisation, it challenges every sacred tradition to rethink what it means to be human, moral, and divine. From Judaism to Hinduism, Christianity to Islam, Buddhism to Sikhism, and from tribal nature worship to Pentecostal revivals, faith communities face a critical choice: resist the algorithm or redeem it. This article explores how ancient religions can embrace AI as an ally of compassion and justice—and concludes with ten practical recommendations for religious leaders to ensure that AI remains the handmaid of modern religion.

The Age of AI and the Crisis of Meaning

Human civilisation stands at a fascinating crossroads. Artificial Intelligence—once the dream of science fiction—has now become a living force shaping everything from medicine to morality, from economics to worship. As machines begin to “think” and “speak” like humans, they awaken deep spiritual questions: What is consciousness? What is the soul? Can wisdom be coded?

AI reflects both the genius and the anxiety of humanity. It mirrors our yearning for mastery and meaning. Yet it also tempts us to forget the divine origin of intelligence itself. Religions must now decide whether AI will serve as a servant of compassion—or a substitute for conscience.

A Mirror to the Soul

In the moral imagination of humankind, intelligence was once the domain of gods and prophets. Now, algorithms predict our desires, compose prayers, and even generate sermons. This provokes the oldest theological inquiry: what distinguishes the human from the mechanical?

Every major religion—Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and others—centres on the sanctity of consciousness. AI therefore challenges not doctrine alone but the very hierarchy of creation. Machines may simulate thought, but can they love, forgive, or worship?

Responses of the Ancient Faiths

Judaism

Rooted in divine wisdom, Judaism sees knowledge as sacred service. AI can amplify Tikkun Olam—the call to repair the world—if used for justice and compassion. But rabbis warn that algorithms interpreting scripture without human heart risk turning revelation into raw data.

Hinduism

In Hindu metaphysics, consciousness (Chaitanya) pervades all creation. Thus, AI could be viewed as a new expression of divine energy—Shakti—if directed towards Dharma (righteous living). Yet the moral challenge remains: can machines, lacking karma and soul, act without moral consequence?

Christianity

Christian thought asks whether machines can ever embody divine image (Imago Dei). Pope Francis has called for a “theology of technology” to ensure AI serves the common good. The Orthodox and Anglican churches echo this concern, warning that empathy and confession cannot be replaced by algorithms. Grace, they remind us, is beyond programming.

Islam

Islam upholds the principle of Khilafah—human stewardship of creation. AI must, therefore, reflect ethical accountability. The Qur’an’s reverence for knowledge (‘Ilm) encourages innovation, yet warns against arrogance (Shirk). AI must serve creation, not dominate it.

Eastern Pathways of Harmony

Buddhism

For Buddhism, mind is a continuum, not a fixed entity. Can an AI experience Dukkha (suffering) or attain Nirvana? Probably not—but it can still be trained in compassion. Buddhist ethics could guide AI development towards mindfulness and benevolence rather than profit and power.

Jainism

Jain values of Ahimsa (non-violence) and self-restraint challenge the exploitative uses of technology. When AI aids sustainability and kindness, it aligns with Jain dharma; when it fuels consumerism and surveillance, it violates it.

Confucianism

Confucian thought emphasises harmony, respect, and virtue. China’s AI policies, often invoking Confucian ideals, risk losing their ethical soul if used for control rather than compassion. The principle of Ren—benevolence—should guide all AI governance.

Faiths of Fire and Spirit

Sikhism

Sikh theology teaches the oneness of God and equality of all beings. AI, used rightly, can serve Seva (selfless service)—educating the poor, empowering women, preserving justice. But if it widens inequality, it betrays the Guru’s vision.

Pentecostal and Evangelical Movements

In Pentecostalism, faith is felt through the living Spirit. While AI may simulate preaching, it cannot replicate divine inspiration. Yet, as a missionary tool—translating scripture, streaming worship, or comforting the lonely—AI can extend the reach of the Gospel.

Voices of the Earth: Indigenous Wisdom

Aboriginal Australians, Native Americans, African animists, and tribal faiths of Asia perceive spirit in every element of nature. To them, AI is both a marvel and a menace. It can document endangered languages, protect ecosystems, and revive ancient wisdom—but if used for extraction or domination, it violates sacred balance. Their message to modernity is timeless: “Technology without reverence is desecration.”

Organised Religions and the Risk of Redundancy

Institutional religions—Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican, and others—face a silent crisis of relevance. Younger generations are turning to digital spaces for meditation and moral guidance. Virtual chaplains and AI confessors now simulate spiritual counsel. The challenge for faith leaders is to reclaim these frontiers, not retreat from them.

As the Church once baptised the printing press, it must now baptise AI with wisdom and compassion.

AI as the Handmaid of Faith

Properly guided, AI can serve religion rather than subvert it. Imagine systems that translate scriptures across cultures, or algorithms that analyse moral teachings to find shared values among faiths. Visualise virtual pilgrimages that bring Mecca, Jerusalem, or Varanasi to those unable to travel. When AI amplifies empathy, preserves sacred heritage, or nurtures the environment, it becomes a new form of prayer—action made intelligent.

The Ethical Imperative

Religious leaders cannot afford silence. They must engage scientists and policymakers in building moral firewalls around technology. The dialogue between monasteries and laboratories, temples and tech parks, should shape the conscience of the 21st century. As medieval scholastics reconciled faith and reason, we must reconcile spirituality and simulation.

Ten Recommendations to Make AI the Handmaid of Modern Religion

- Form Global Interfaith AI Ethics Councils – Unite theologians and technologists to develop shared moral principles.

- Preserve Sacred Heritage Digitally – Employ AI to archive, restore, and translate ancient scriptures and oral traditions.

- Educate Clergy on Digital Ethics – Include AI literacy in seminaries, monasteries, and madrasas.

- Promote Compassionate Algorithms – Train AI models on moral literature to embed empathy into design.

- Deploy AI for Ecological Protection – Use predictive data to safeguard forests, rivers, and sacred landscapes.

- Define Boundaries for AI in Worship – Keep prayer, confession, and blessing as sacred human acts.

- Bridge the Digital Divide – Ensure rural and marginalised communities access spiritual technologies.

- Engage Youth through Digital Faith Platforms – Harness AI creativity for intergenerational dialogue and service.

- Encourage Interfaith Harmony – Let AI reveal ethical common ground among world religions.

- Reaffirm the Supremacy of the Human Soul – Declare that while machines can think, only humans can love, forgive, and commune with the Divine.

Conclusion

The rise of AI is not a threat to faith but a test of it. If guided by conscience, AI can help humanity rediscover awe—the very essence of spirituality. But if left unchecked, it may erode the mystery that binds us to the Divine.

The call before the world’s faith leaders is clear: let technology serve transcendence, not replace it. In doing so, we ensure that AI becomes not our master, but our humble handmaid of modern religion.

Beyond the Smoke: Physical and Metaphysical Dimensions of Stubble Burning in North India

By Dr. K. M. George

Secretary General, Global Millets Foundation & CEO, Sustainable Development Forum

Email: melmana@gmail.com

Abstract (150 words)

Stubble burning in North India is an annual ritual that transcends mere agricultural practice, affecting public health, urban life, and climate resilience. While farmers perceive it as an economic necessity to prepare fields for the next crop cycle, the resulting smoke engulfs cities like Delhi in toxic haze, elevates respiratory illnesses, and exacerbates climate change. Beyond these tangible consequences, stubble burning holds deeper socio-cultural and metaphysical dimensions, reflecting systemic inequities, governance gaps, and a human-environment disconnect. This article analyzes the historical context, farmer compulsions, urban fallout, environmental impacts, and policy responses to stubble burning. It proposes a comprehensive framework balancing technological interventions, economic incentives, regulatory enforcement, and cultural awareness. Comparative tables highlight crop-residue alternatives and millet-based crop systems that offer both environmental and socio-economic benefits. The article concludes with a roadmap integrating carrot-and-stick approaches, urging holistic action to transform this recurring crisis into an opportunity for sustainable agriculture and climate-conscious living.

Introduction

Each winter, the golden fields of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Rajasthan are engulfed in smoke, as farmers set paddy stubble ablaze to prepare their fields for wheat sowing. The sight is striking, almost ritualistic, yet behind this ephemeral beauty lies a complex interplay of agricultural necessity, urban health crises, and environmental stress. The issue is not merely a matter of smoke drifting across borders—it is a manifestation of systemic failures in policy, infrastructure, and social equity.

Stubble burning has physical impacts—air pollution, health hazards, and greenhouse gas emissions—but its metaphysical dimensions are equally compelling. It exposes the disconnect between rural livelihoods and urban well-being, the fragility of ecological ethics, and the broader philosophical questions about humanity’s stewardship of the environment. This article delves into these multiple dimensions to provide a balanced and comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Historical Context

Stubble burning is not a modern innovation. Traditional Indian agriculture involved residue management through manual ploughing and composting. The advent of high-yield varieties and mechanized harvesting in the Green Revolution introduced short-duration paddy crops that leave behind dense residues, creating logistical challenges for farmers. Over the decades, stubble burning evolved from an occasional practice into an entrenched agricultural habit, shaped by economic pressure, labor shortages, and inadequate mechanized alternatives.

Farmer Compulsions

Understanding the farmer’s perspective is essential. The window between paddy harvest and wheat sowing is narrow—often just 15–20 days. Delayed sowing can reduce wheat yield by up to 10–15%. The lack of affordable, efficient residue-management technology compels farmers to adopt burning as the fastest, most economical solution. Financially, the cost of mechanized solutions like Happy Seeders, rotavators, and mulchers is prohibitive for smallholders, while government subsidies remain inconsistent.

Socio-economically, farmers face a dual pressure: market expectations to maximize yield and the physical demand to prepare fields quickly. In this context, stubble burning becomes not merely a choice but a survival strategy.

Urban Fallout and Health Impacts

The smoke generated by stubble burning contains particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and other toxic compounds. This pollution drifts over cities, contributing to hazardous air quality levels, respiratory illnesses, and even cardiovascular diseases. Delhi and surrounding urban centers witness a surge in hospital visits, school closures, and public health emergencies during the peak burning months of October and November.

Beyond immediate health effects, stubble smoke exacerbates climate change by releasing black carbon and methane, which accelerate warming. The urban-rural divide becomes palpable: rural farmers bear the economic burden, while urban populations endure the environmental consequences.

Metaphysical Dimensions

Stubble burning is also a metaphor for the larger ethical and philosophical dilemmas of human-nature interaction. It raises questions about:

Equity: Who bears the cost of unsustainable practices—rural laborers or urban citizens?

Governance: How effective are policy frameworks that penalize farmers without providing practical alternatives?

Cultural Disconnect: How can traditional agricultural wisdom coexist with modern efficiency demands?

In essence, stubble burning reflects the moral challenge of balancing immediate human needs with long-term environmental stewardship.

Policy Critique

India’s policy landscape has oscillated between punitive and incentive-based measures. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has issued fines and strictures, yet enforcement is challenging given the socio-economic context. Subsidy schemes for mechanized solutions exist, but inconsistent distribution, bureaucratic delays, and limited awareness hinder uptake.

International experience offers lessons. For instance, in the European Union, integrated crop-residue management and direct seeding have reduced open-field burning substantially. Lessons include the importance of:

Subsidies linked to technology adoption rather than mere availability

Localized farmer training programs

Market incentives for crop residues as biofuel, fodder, or compost

Comparative Table: Positive vs. Neutral Millets for Residue Management

Crop Type Residue Volume Environmental Impact Nutritional/Market Value Applicability in Stubble Management

Sorghum (Jowar) Low Minimal High fiber, high demand Suitable for mechanized harvesting

Pearl Millet (Bajra) Moderate Low Rich in protein & iron Can reduce paddy residue dependency

Paddy High High PM2.5, GHG Staple, moderate demand Requires mechanized management

Foxtail Millet Low Low Highly nutritious Eco-friendly alternative

Alternatives to Stubble Burning

Several technological and agroecological interventions can reduce stubble burning:

Mechanical Solutions: Happy Seeder, rotavators, and mulchers allow direct sowing into residue-covered fields.

Bio-based Solutions: Conversion of stubble into biochar, compost, and animal fodder.

Agroforestry and Millet Diversification: Integrating millets reduces residue volume and enhances soil health.

Economic Incentives: Carbon credit schemes for farmers adopting residue management practices.

Community Awareness: Farmer cooperatives and educational campaigns to foster sustainable practices.

Carrot-and-Stick Roadmap

A holistic approach requires both incentives and enforcement:

Carrot: Subsidized mechanization, carbon credits, and market development for bio-residues.

Stick: Strict but context-sensitive enforcement of penalties, complemented by monitoring and early warning systems.

Integration: Linking agricultural banks, insurance providers, and local governance to create a seamless support system.

Conclusion: Beyond the Immediate Smoke

stubble burning in North India is more than an environmental or health issue; it is a mirror reflecting systemic socio-economic inequities and ethical dilemmas in human-nature interaction. Addressing it requires transcending simple blame or regulation, moving instead toward holistic, inclusive, and culturally informed solutions.

The call is urgent: to invest in farmer-friendly technology, create economic pathways for residue utilization, and cultivate environmental consciousness across rural and urban spheres. Only then can the smoke that clouds our skies be replaced by a vision of sustainable agriculture, climate resilience, and shared responsibility.

The future beckons—include and prosper, or exclude and perish.

Bridging the AI Technology Gap Before It Becomes a Chasm

By Dr K.M. George — Secretary-General, Global Millets Foundation & CEO, Sustainable Development Forum

The world is living through a paradox. Never before have we witnessed such extraordinary leaps in technology, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI). Yet never before has the risk of exclusion been so stark. While AI transforms health, education, commerce and governance in advanced economies, large parts of the globe remain on the margins — struggling with basic digital infrastructure, skills shortages, and limited say in shaping the rules of the game.

This is not just a “digital divide” anymore. It is an AI divide, growing faster than many policymakers realize. Left unchecked, it will deepen inequality between nations and within societies. The United Nations’ recent Governing AI for Humanity report makes it clear: without urgent, coordinated action, the very technology that could help us solve global challenges may instead amplify them.

From Access to Capability: How the Divide Evolved

The digital divide of the 1990s and 2000s was about simple access: who had internet, who had devices. Over time, mobile phones and cheaper data services narrowed that gap. But the story didn’t end there.

The new divide is about capability. Can teachers use AI to prepare students for tomorrow’s jobs? Can hospitals in low-resource settings deploy AI diagnostics to catch diseases early? Can small farmers use satellite-fed AI tools to boost yields?

For many, the answer is still no — not because they lack imagination, but because they lack infrastructure, skills, data, and investment. The AI revolution, concentrated in a few labs and companies in a handful of countries, risks leaving billions of people as passive consumers of systems they had no part in shaping.

The Reality Check: Uneven AI Adoption

Recent reports from the World Bank, OECD, and UN agencies paint a sobering picture:

- Adoption is lopsided. Firms in wealthy countries are adopting AI at lightning speed. In some regions, adoption doubled in a year. Meanwhile, many developing countries lag far behind.

- Wages are at risk. OECD economists warn that AI could widen wage inequality if workers are not reskilled. Some tasks will be automated, while others will demand higher skills and pay premiums.

- Basic infrastructure is missing. Billions remain offline or dependent on unreliable internet. Without reliable electricity, broadband, and data centers, AI remains a distant dream.

- Literacy is low. UNESCO stresses that “AI literacy” is now essential. Without it, communities risk becoming an “AI underclass” — unable to interpret, evaluate, or benefit from the tools shaping daily life.

- Women are especially vulnerable. Gender gaps in digital access and employment mean women could be disproportionately displaced by AI-driven disruption.

These realities mean AI isn’t just an innovation story. It’s a development story. And development gaps, if ignored, have a way of hardening into permanent divides.

The Challenges We Cannot Ignore

- Concentration of power. A handful of corporations control the compute, data, and models that underpin modern AI. This centralization risks embedding their priorities into systems used globally.

- Job dislocation. AI will not just replace jobs — it will reshape them. Without proactive policy, entire communities may find themselves locked out of the AI economy.

- Governance vacuum. Many countries lack even the most basic AI policies or data protection laws. Without them, they risk becoming “rule takers” in a game set by others.

- Exclusion by design. If AI systems don’t recognize local languages, cultural contexts, or social needs, they effectively exclude those communities.

- Gendered impact. Without deliberate empowerment, women risk falling even further behind. Already underrepresented in STEM and leadership, women face greater displacement risks in routine sectors — from clerical work to retail.

📦 BOX COLUMN: AI Through a Gender Lens

The Concern

Technology gaps are never gender-neutral. Women — especially in low- and middle-income countries — often have less access to devices, weaker digital skills, and fewer opportunities in high-paying tech sectors.

The Opportunity

AI can empower women:

- Entrepreneurship: Market access, financial planning, e-commerce support.

- Education: AI tutors and translation tools for girls in rural areas.

- Health: AI-driven diagnostics for maternal care where female doctors are scarce.

- Safety: Platforms that strengthen reporting and prevention of gender-based violence.

The Call to Action

- Scholarships for women in STEM.

- Quotas in AI policy committees.

- Investment in women-led AI startups.

A gender lens is not optional. It is essential for inclusive AI.

What Must Be Done: A Seven-Point Agenda

The answer is not to slow down AI. The answer is to speed up inclusion:

- Invest in digital foundations. Last-mile broadband, affordable devices, reliable electricity, and public data platforms.

- Launch national AI programs. Labs, sandboxes, fellowships — AI solutions tailored to local realities: agriculture, health, disaster response.

- Reskill and protect workers. Wage inequality is not inevitable. Targeted reskilling, apprenticeships, and social safety nets are essential.

- Democratize data and models. Open repositories and regional “AI clouds” give universities, SMEs, and governments affordable access.

- Adopt inclusive governance. Algorithmic audits, transparent procurement, and global standards.

- Make AI literacy universal — with a gender lens. From classrooms to community centers, training in local languages ensures no one is left behind.

- Pool global financing. A global AI capacity fund — much like climate finance — can support infrastructure, skills, and governance in the Global South, with earmarked resources for gender empowerment.

📦 BOX COLUMN: AI and Education — Double-Edged Sword

The Concern

AI is transforming learning — but not always positively. Students may rely on AI shortcuts, bypassing critical thinking and research skills.

Risks for Formal Education

- Over-reliance on AI reduces original thinking.

- Erosion of critical analysis, problem-solving, and reasoning skills.

- Equity gaps: Students without AI access fall behind.

- Teacher challenges: Need to adapt assessment and pedagogy.

The Opportunity

AI can enhance learning if guided properly:

- Personalized tutoring for individual learning pace.

- Assistance in research, simulations, and language translation.

- Tools for teachers to provide targeted feedback.

Call to Action

- Integrate AI literacy into curricula.

- Train teachers to supervise AI usage responsibly.

- Design assignments that encourage original thinking.

- Ensure equitable access, especially in under-resourced schools.

Bottom Line

AI is not anti-educational — but without careful guidance, it risks undermining formal learning foundations.

Proof That It Works: Early Success Stories

Inclusive AI is already showing impact:

- Health: AI-assisted radiology tools help under-staffed hospitals triage cases faster.

- Agriculture: Satellite-driven advisory systems support small farmers, including women.

- Languages: Localized AI models make government services accessible in minority languages.

- Women in leadership: Programs in Africa and South Asia train women entrepreneurs in AI, with measurable success.

These pilots, if scaled, can provide replicable models for broader deployment.

What to Measure: Tracking Progress

Governments and donors should track:

- Broadband access with real usability.

- AI adoption among SMEs, not just tech giants.

- Wage gaps in AI-intensive industries.

- AI literacy levels among public professionals.

- Gender parity in digital access, AI training, and leadership roles.

These metrics ensure that AI advances shared opportunity, not entrenched inequality.

The Political Economy of AI: Who Wins, Who Resists

Countries and companies with a head start will protect their advantages. They may resist open models, global standards, or redistributive funds.

Coalitions matter. Governments, donors, civil society, and responsible businesses must act together. Incentives (funding, partnerships) and obligations (audits, licensing, standards) can align cooperation. The UN’s call for multilateral AI governance — including a global capacity-building fund — is a starting point, but urgent operationalization is critical.

A Turning Point, Not a Foregone Conclusion

AI is not destiny. It is a set of choices.

We can let the divide widen, leaving billions behind. Or we can invest in digital infrastructure, reskill workers, empower women, safeguard education, and democratize access. Done right, AI can be an engine of shared prosperity. Done wrong, it will entrench inequality.

The technology is moving fast. Our response must move faster.

COP 30 and Its Challenges for the Global South: A Roadmap for Humanity’s Survival

By Dr. K.M. George – Secretary General, Global Millets Foundation and CEO, Sustainable Development Forum

Introduction: COP 30 in Historical Context

The Conference of the Parties (COP) under the UNFCCC has, for nearly three decades, provided the global stage where the climate future of our planet is negotiated. With COP 30 set to convene in Belém, Brazil, in 2025, the Global South finds itself both at the epicentre of climate vulnerabilities and at the forefront of possible solutions. Unlike previous conferences, COP 30 holds heightened urgency. The Amazon rainforest, often called the “lungs of the Earth,” and the vast ecosystems of the Global South are under severe strain, reflecting the clash between developmental aspirations and ecological limits.

COP 30’s genesis lies in the growing frustration that previous COP summits have produced commitments, but insufficient action. The climate financing gap remains wide, carbon emissions continue to rise, and global temperatures edge perilously close to the 1.5°C threshold. The conference thus comes not merely as another diplomatic negotiation but as a survival platform for humanity—demanding sacrifices from the Global North and resilience-building in the Global South.

Shared Challenges in an Unequal World

The challenges of climate change do not affect all countries equally. The Global South bears disproportionate burdens, despite contributing the least historically to greenhouse gas emissions. The following key challenges illustrate this inequity:

- Youth Unemployment and Climate Migration

- Rising sea levels, cyclones, droughts, and floods are displacing millions, creating climate refugees.

- Youth unemployment in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America collides with environmental degradation, fuelling despair and migration.

- The lack of green jobs and vocational training hampers young people’s capacity to lead in climate adaptation and mitigation.

- Inflation and Economic Instability

- Food inflation skyrockets when floods destroy crops or droughts reduce yields.

- Energy price volatility worsens economic inequity in developing nations.

- Poorer households spend a disproportionate share of income on food, making them highly vulnerable to climate shocks.

- Shrinking Arable Land

- Reckless land use, urban expansion, and soil degradation are reducing fertile land.

- Excessive groundwater exploitation—especially for water-intensive crops like sugarcane—leads to long-term desertification.

- Crop failures trigger distress sales, perpetuating rural poverty.

- Frequent Natural Calamities

- Cyclones, earthquakes, flash floods, and landslides occur with greater frequency.

- Infrastructure damage strains already limited resources.

- Small island developing states (SIDS) face existential threats.

- Unsustainable Farming Practices

- Stubble burning worsens air quality across regions like South Asia.

- Monocropping and indiscriminate pesticide use weaken soil and biodiversity.

- Heavy reliance on groundwater creates ecological imbalances.

- Deforestation and Ecological Destruction

- Reckless felling of trees destroys carbon sinks.

- Amazon deforestation accelerates biodiversity loss.

- The destruction of mangroves heightens coastal vulnerability.

Implications for the Rich and Poor Alike

While the Global South experiences the most acute impacts, the ramifications ripple across the world:

- Rich countries face migration pressures, global supply chain disruptions, and food security risks.

- Poor countries suffer immediate humanitarian crises, loss of livelihoods, and governance challenges.

- Global finance systems are destabilized by disaster-induced economic shocks.

The interdependence of the global economy means that no country—rich or poor—remains insulated from climate breakdown.

Recommendations: A Roadmap Forward

To move beyond declarations and towards tangible survival strategies, COP 30 must focus on equity, sacrifice, and transformation. Below are proposed solutions:

- Climate Finance and Debt Justice

- Rich countries must fulfill and expand the $100 billion annual climate finance pledge.

- Debt-for-climate swaps should be introduced to free fiscal space in developing nations.

- Establish a Loss and Damage Fund with clear accountability.

- Green Jobs for Youth

- Large-scale investment in renewable energy, agroecology, and ecosystem restoration.

- Global apprenticeships and vocational training programs for climate-smart agriculture.

- Incentives for youth entrepreneurship in sustainability sectors.

- Agricultural Transition

- Promote climate-resilient crops like millets, pulses, and sorghum.

- End unsustainable subsidies for water-intensive crops.

- Support agroforestry and regenerative farming.

- Technology Transfer and Innovation

- Facilitate affordable access to clean energy technologies in the Global South.

- Encourage public–private partnerships for sustainable innovations.

- Build digital platforms for smallholder farmers to access climate data.

- Disaster Preparedness and Resilience

- Early warning systems for floods, cyclones, and droughts.

- Community-based disaster risk management strategies.

- Build resilient infrastructure in vulnerable regions.

- Forest and Ecosystem Protection

- Establish global moratoriums on reckless deforestation.

- Pay indigenous communities for ecosystem services.

- Expand protected areas and reforestation projects.

- Global Governance and Equity

- COP 30 should establish binding frameworks for emission cuts by major polluters.

- Create mechanisms for accountability in climate pledges.

- Ensure equitable participation of Global South voices in negotiations.

- Reimagining the Carbon Credit Regime

- Make carbon markets more inclusive by prioritizing projects from the Global South, ensuring that smallholder farmers, indigenous peoples, and community-based initiatives benefit directly.

- Introduce a Fair Carbon Price mechanism that accounts not only for carbon sequestration but also for biodiversity protection and water conservation.

- Simplify certification procedures so that rural cooperatives and small communities can access carbon credit revenues without prohibitive transaction costs.

- Encourage corporate buyers in the Global North to commit to long-term partnerships with Global South communities, transforming credits from a short-term offset tool into a sustained development driver.

- Establish transparency mechanisms to ensure that carbon credit revenues are reinvested locally in education, health, and climate-resilient infrastructure.

Pinpointed Responsibilities of the Global North and Global South

Tasks for the Global North:

- Rapidly decarbonize industries, transport, and energy sectors to meet net-zero targets.

- Honor climate finance commitments with predictable, accessible, and scaled-up funding.

- Share clean technologies without restrictive patents, enabling wider adoption in the South.

- Reduce excessive consumption patterns that drive ecological degradation.

- Support adaptation and relocation efforts for vulnerable communities in SIDS and low-lying regions.

- Invest in reforestation and biodiversity projects that deliver global benefits.

Tasks for the Global South:

- Transition from unsustainable farming to climate-smart and regenerative agriculture.

- Invest in renewable energy infrastructure to reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

- Strengthen governance to ensure transparency in climate finance utilization.

- Empower youth with skills and opportunities in green sectors.

- Protect indigenous knowledge and integrate it into climate solutions.

- Prioritize community-based adaptation strategies to build resilience against natural disasters.

- Enforce sustainable land use policies to curb deforestation and groundwater depletion.

Conclusion: Toward a Shared Future: Toward a Shared Future

COP 30 is more than a diplomatic conference—it is humanity’s trial by fire. The sacrifices of the Global North in reducing consumption, emissions, and ecological footprints must be matched by the resilience and innovation of the Global South. Youth, farmers, indigenous peoples, and marginalized groups must be brought from the margins to the center of climate action.

The road to survival is neither easy nor short. It requires sacrifices, structural changes, and global solidarity. The time for half-measures is over; the destiny of both rich and poor is intertwined. As COP 30 convenes in the Amazon, the symbolism is clear: either we safeguard our common home or watch it perish. The choice is collective, and the time is now.

The future beckons—shall we falter, or shall we rise? The clarion call is before us; history will judge whether we acted with courage or complacency. The moment is ours to seize, for the survival of our planet and the dignity of generations yet unborn.

Like a torch passed from one age to another, the fire of responsibility now rests in our hands. We must choose not with hesitation but with boldness. Include and prosper, or exclude and perish.

Counting the Nation, Digitally: Why Kerala’s Hills, Plains and Ports Are at the Heart of India’s 2027 Census Rehearsal

By Dr K. M. George, CEO, Sustainable Development Forum

melmana@gmail.com

A historic headcount, seven years in the waiting

After an unprecedented delay of seven years, India’s population census—the single largest administrative exercise in human history—is returning to the field. The Census of India 2027, to be rolled out in two phases between 2026 and 2027, is poised to mark a technological and methodological watershed.

For the first time, the entire enumeration will be conducted primarily through digital tools—tablets, mobile apps and online self-reporting—ushering in a paradigm shift in how demographic and socio-economic information is collected, verified and aggregated in the world’s largest democracy.

Before the actual enumeration begins, however, the Census Directorate will conduct a national pre-test or ‘dress rehearsal’ between 11 and 30 November 2025 (with self-enumeration open from 1 to 7 November). This critical pilot will test the revised questionnaires, field methodologies and digital platforms in selected sample areas across every State and Union Territory.

In Kerala, three districts—Ernakulam, Idukki and Thrissur—have been earmarked as the sample units for this pre-test. Their selection is far from arbitrary: taken together, they reflect the State’s astonishing diversity of geography, settlement and digital readiness.

Three districts, three worlds

The logic behind the choice of these three districts illustrates the Census Office’s broader sampling philosophy: to test its instruments across contrasting social, geographic and infrastructural conditions.

- Ernakulam, the nerve-centre of Kerala’s urban economy and home to the port city of Kochi, represents dense metropolitan conditions, high levels of migration, and advanced digital infrastructure.

- Thrissur, lying at the heart of the State, embodies semi-urban transition—town clusters surrounded by agrarian hinterlands, with both traditional and modern occupations coexisting.

- Idukki, on the other hand, is the State’s mountainous interior—a district of forested slopes, tribal hamlets, hydropower projects and limited connectivity.

Together they simulate the spectrum of challenges that the national census must grapple with: the complexities of urban density, the fluidity of peri-urban growth, and the remoteness of highland settlements. Testing digital enumeration tools in these varied contexts will allow the Directorate to refine the questionnaire design, app functionality and enumerator training well before the 2027 rollout.

What the pre-test really means

The census pre-test is not a miniature census in itself; it is a methodological laboratory. Conducted in a limited number of enumeration blocks in each participating district, it is designed to identify problems before they magnify on a national scale.

Enumerators and supervisors will test every aspect of fieldwork:

- clarity of the digital forms,

- navigation of skip patterns and conditional logic,

- syncing of offline data in low-connectivity areas,

- handling of self-enumeration entries by citizens, and

- integration of new variables such as caste, digital access and modern housing amenities.

Feedback loops are built into the process. Supervisors will audit samples of filled forms, technical teams will track upload failures, and field debriefings will document both human and software challenges. After tabulation, a comprehensive technical evaluation will recommend corrections—ranging from question wording and training modules to interface redesign and backup procedures.

Selecting the sample: a matter of representativeness

While official documents have not publicly disclosed the full criteria for district selection, long-standing census methodology points to several guiding assumptions:

- Diversity of terrain and settlement. Pre-test locations must represent urban, rural and remote areas, including hilly, forested and coastal zones.

- Variation in digital readiness. Areas with both strong and weak connectivity must be included to test offline data-capture features.

- Administrative complexity. Regions experiencing boundary changes or overlapping jurisdictions are essential for checking mapping accuracy.

- Linguistic and cultural variation. Multi-lingual and multi-caste contexts test translation consistency and enumerator comprehension.

- Operational feasibility. The chosen districts must also offer administrative support and accessibility for supervision.

Kerala’s trio neatly fulfils these assumptions. In the national context, each state and Union Territory is expected to identify one to three such districts. Across India, therefore, roughly 50 to 100 districts—or selected sample blocks within them—are likely to participate in the pre-test.

The anatomy of an enumeration

The Census of India operates in two major phases:

- House listing and Housing Census – cataloguing every structure, household and dwelling unit, and noting housing characteristics such as water source, sanitation, fuel, lighting, internet access and vehicle ownership.

- Population Enumeration – counting every individual as on the reference date, recording details of age, sex, education, occupation, migration, language, and now, caste.

For 2027, the reference date for most of the country is 00:00 hours, 1 March 2027, while snow-bound or non-synchronous areas (in the Himalayan and North-Eastern regions) will be enumerated with 1 October 2026 as the reference date.

The house listing phase is scheduled to begin in April 2026, paving the way for the Population Enumeration in early 2027. The pre-test a year earlier thus serves as a full rehearsal for both phases, albeit in miniature.

Digital by default, paper as backup

The Census 2027 will be India’s first fully digital headcount. Enumerators will carry tablets or mobile devices preloaded with multilingual digital questionnaires, equipped with offline data-entry capability and automatic sync once connectivity is restored.

For the first time, households will have the option of self-enumeration—entering their own information through a secure online portal during the house listing phase. This is intended to reduce the enumerators’ workload and empower digitally literate citizens to participate directly.

However, recognising India’s digital divide, the Directorate has wisely retained paper schedules as a fallback. In remote or connectivity-poor areas—such as parts of Idukki or the North-East—enumerators may revert to paper, with later data entry at designated upload centres. The hybrid model is a pragmatic compromise between ambition and ground reality.

Manpower and magnitude

Although the exact all-India figure for field personnel has not been officially announced, internal estimates and precedent suggest the deployment of around 3.3 million enumerators and supervisors nationwide—comparable to the workforce of the 2011 Census.

Each enumerator typically covers about 150 to 180 households within an enumeration block over a two-week period. Given an average of 25–30 minutes per household (depending on family size and complexity), this represents an immense coordination exercise even before digital complexities are added.

Training is therefore critical. Enumerators must master both the content and the device—navigating multiple screens, local language inputs, and troubleshooting on the field. The pre-test will reveal whether current training modules suffice or need expansion.

Counting rupees: the cost of enumeration

The Government of India has not yet disclosed a revised budget for Census 2027. The 2021 census, postponed due to the pandemic, had an estimated allocation of around ₹8,754 crore, which is likely to rise substantially owing to inflation, device procurement and digital infrastructure costs.

However, digital enumeration is expected to yield long-term savings. Once the initial investment in hardware, software and secure data architecture is made, future censuses and surveys can reuse these systems, reducing the recurring cost of printing, transport and manual data entry. Moreover, faster digitisation enables real-time error checking and earlier release of data—a chronic weakness in previous censuses.

New questions for a new India

Beyond technology, the 2027 census introduces new content dimensions reflecting the changing social and economic landscape.

- Caste Enumeration: For the first time in over seven decades, the population enumeration will include a comprehensive caste question, responding to long-standing demands from states and social groups for updated data on caste composition.

- Digital Connectivity: Questions on internet access, smartphone ownership and digital literacy are expected, aligning with the government’s focus on digital inclusion.

- Sustainability Indicators: Expanded housing schedules are likely to capture waste management, renewable-energy use and water-harvesting practices—critical for sustainable-development metrics.

- Migration and Urbanisation: Post-pandemic mobility patterns, remote work and trans-state migration require new tracking mechanisms.

- Gender and Disability Inclusion: Improved wording and coding for gender diversity and disabilities reflect both policy emphasis and international statistical standards.

Thus, the 2027 Census is not merely an update of 2011; it is a recalibration of what the nation chooses to know about itself.

Contrasts with 2011: from paper to pixels

India’s last census, conducted in 2011, relied entirely on paper schedules. Enumerators carried bundles of printed forms, filled them manually and later shipped them to scanning centres where optical character recognition was applied—a time-consuming process that delayed data release by years.

By contrast, the 2027 exercise promises real-time digital capture, geo-tagging of households, and instant aggregation at supervisory levels. Errors can be flagged instantly, and enumerator performance monitored through dashboards.

Self-enumeration adds a new participatory dimension, though it also raises questions of verification and data security. To address privacy concerns, the Directorate has emphasised encryption and restricted data access, alongside stringent penalties for unauthorised use.

Kerala as a microcosm of census challenges

Kerala presents a particularly revealing terrain for testing the digital census. Its near-universal literacy, strong local governance, and extensive digital penetration make it ideal for trialling self-enumeration and mobile apps.

Yet the State also poses logistical puzzles:

- High population density in coastal cities like Kochi complicates boundary demarcation;

- Scattered hill hamlets in Idukki challenge device connectivity;

- Large expatriate populations generate questions about residency and migration classification; and

- Multiple dwelling ownership (urban apartments and rural ancestral homes) complicates the concept of “usual residence.”

If the digital census can perform robustly across this range—from Kochi’s high-rises to Idukki’s highlands—it will likely succeed anywhere in India.

From the field: what the pre-test will reveal

The forthcoming November 2025 pre-test will serve as a stress test for the entire apparatus. Based on previous pilots, typical issues expected to surface include:

- Questionnaire clarity: Ambiguities or misinterpretations will be identified and rectified.

- Software glitches: App crashes, battery drain, or sync failures will be logged for correction.

- Training gaps: Enumerators’ comfort with devices and skip logic will be assessed.

- Public engagement: Response rates to self-enumeration and citizen awareness levels will be measured.

- Mapping accuracy: Verification of enumeration block boundaries, particularly in newly formed wards and villages.

- Workload estimation: Actual time per household will be measured to recalibrate workload norms.

Once the results are collated, the Directorate will refine the instruments, retrain field staff and revise operational manuals before the main census.

Behind the numbers: assumptions and expectations

Every census rests on several statistical and logistical assumptions:

- That every person can be linked to one and only one household on the reference date.

- That administrative boundaries remain frozen during enumeration to prevent duplication or omission.

- That enumerators are impartial and well trained, capable of handling linguistic and cultural diversity.

- That digital tools will not bias coverage against those with poor connectivity or limited literacy.

The pre-test will reveal whether these assumptions hold in practice. If digital enumeration produces systematic gaps—for instance, undercounting in remote or elderly populations—mitigation measures such as extended field time or parallel paper schedules can be introduced.

Why pre-testing matters

The scale of India’s census means that even minor design flaws can have massive ripple effects. A poorly worded question can misclassify millions; a faulty app can paralyse an entire district’s enumeration.

Pre-testing acts as the system’s immune response—detecting weaknesses before the full-body operation begins. It also builds enumerator confidence, fine-tunes public communication, and strengthens inter-departmental coordination between the Census Directorate, state governments and local bodies.

In essence, it transforms what could have been a one-off exercise into an iterative process of learning and adaptation.

From data to development

Beyond its statistical intrigue, the census remains the foundation of governance. Every major planning exercise—be it delimitation of constituencies, allocation of central funds, or monitoring of Sustainable Development Goals—depends on accurate census data.

For Kerala, updated census data will underpin urban planning, migration management and disaster-preparedness strategies. For the country, it will recalibrate denominators in per-capita indicators and shape future social and fiscal policy.

The inclusion of caste and digital-connectivity variables also holds implications for equity and inclusion policies, helping to map who remains excluded from India’s growth story.

Learning from the pandemic delay

The long postponement of the 2021 census, owing to COVID-19, inadvertently provided a window for technological innovation. During these years, India has witnessed a digital revolution—from the expansion of Aadhaar and mobile banking to e-governance portals. The census now seeks to ride that wave, transforming a 150-year-old paper tradition into a real-time, interactive data system.

Yet this transition is not without risks. Digital dependence amplifies concerns over data privacy, cybersecurity and potential exclusion of the digitally marginalised. The census must therefore balance efficiency with inclusiveness, ensuring that every voice—digital or not—is counted.

Expected corrections after the pre-test

Once the November 2025 pre-test concludes and its results are analysed, several layers of correction are likely to follow:

- Questionnaire refinement: Simplifying language, adjusting skip sequences and clarifying instructions.

- Application redesign: Improving interface, local language rendering and offline synchronisation.

- Training revision: Incorporating feedback into enumerator manuals and e-learning modules.

- Operational tweaks: Adjusting enumeration block size, revising workload norms, and re-aligning supervisory ratios.

- Communication enhancement: Strengthening public-awareness campaigns to boost self-enumeration participation.

- Backup planning: Refining paper-fallback and contingency logistics for device failures.

- Boundary corrections: Using GIS feedback to rectify overlapping or missing blocks.

These corrections will form the final blueprint for the 2026–27 operations.

Looking ahead: towards a data-intelligent nation

When the first digital census is finally completed, India will possess not only an updated population count but also a dynamic, geo-referenced demographic database—capable of supporting local governance, disaster response and policy innovation at unprecedented granularity.

The success of this transformation, however, depends less on technology than on trust. Citizens must believe that their data are secure and that enumeration serves a collective public good. Enumerators must see themselves not merely as data collectors but as ambassadors of that trust.

If these conditions hold, the 2027 Census could become a model for other large democracies—demonstrating how a nation of 1.4 billion can reinvent its statistical foundations for the digital age.

The road from pre-test to policy

In this light, the choice of Kerala’s Ernakulam, Thrissur and Idukki as testing grounds takes on symbolic significance. They are not just administrative conveniences; they are microcosms of the challenges and possibilities of 21st-century India—urbanisation, migration, connectivity and inclusiveness.

Their lessons will shape not only how India counts its people, but also how it plans for them—balancing precision with participation, technology with empathy.

As the enumerators set out this November 2025 with tablets in hand, they will carry more than devices; they will carry the weight of a nation’s demographic self-portrait. The outcome will determine whether the Census 2027 becomes merely a statistical event—or a transformative act of collective self-knowledge.

Kerala Skill Development and Entrepreneurship University (KSDEU): Vision 2031

Policy Paper by Dr K. M. George

CEO – Sustainable Development Forum & Secretary-General, GMF

Former United Nations Professional

Executive Summary

Kerala, though globally acclaimed for its high literacy and health indicators, faces a paradox that continues to challenge its development narrative. The state’s higher education and skill development ecosystem, despite widespread access, fails to consistently achieve global standards of quality, employability, and innovation. The proposed Kerala Skill Development and Entrepreneurship University (KSDEU), envisioned under Vision 2031, seeks to transform this landscape through a model of education rooted in entrepreneurship, vocational excellence, applied research, and innovation-led growth.

However, Kerala’s structural barriers — including declining academic quality, persistent youth migration to Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, as well as entrenched political interference and the overwhelming dominance of private autonomous colleges — represent critical threats. Without deliberate, phased, and measurable strategies, KSDEU risks becoming yet another high-profile but underperforming institution that produces graduates ill-equipped for the realities of a competitive global labour market.